Bottlenecks in Funding Longevity

With Longevity Science Exploding, Why Isn't Funding Following Suit?

Disclaimer: Not investment advice. The views expressed are solely the opinion of the author and not representative of any entity they are affiliated with.

It is hard to think of something with a larger demand than products extending the human lifespan. After all, aging is something that unites all of us, and something people universally want to avoid - at least its negative side effects. Few people would not want to live longer, as many surveys (such as this one) show. The economies predicted for the emerging lifespan extension field are breathtaking as well - according to one study, a single year of extended lifespan is worth $38 trillion, while a more recent market estimation by age1 estimates $150-200 billion in peak sales from a single drug approved and marketed for aging.

However, as anyone in the longevity biotech field can attest, funding is definitely not growing on trees - in fact, the largest inter-field survey of professionals in the longevity biotech community, the Longevity Bottlenecks study, has found 'Overall lack of funding' to be the top bottleneck alongside 'Validated Biomarkers'. Why can that be, if extended healthspan and lifespan is something every single person on the planet wants and the return potential is massive? As a person who finds himself on the venture side of the negotiating table, I have a few thoughts.

Regulatory Uncertainty

If you take another look at that Longevity Bottlenecks study, you will notice that regulatory uncertainty is actually the main bottleneck for investors in the space. Many longevity maximalists state that regulations should be relaxed or lifted altogether to advance longevity research. While I do agree that some aspects could be streamlined better, regulations are necessary to protect people. It’s just that the longevity/healthspan thesis is not very compatible with the way regulatory guidelines work in the first place.

The core problem here is that the regulatory frameworks are optimized to show results quickly - you give a drug, and you see an improvement over control within the constraints of the trial. This does not really work for therapeutics that extend lifespan, since the effects would take much longer to surface, hence the trial would need to take much longer, skyrocketing the budgets.

One could expedite the process by recruiting more people in the first place - similarly how the vaccine trials work by showing a decrease in the incidence of a particular infectious disease, longevity therapeutic trials showing multi-morbidity prevention, such as the famous TAME trial, could cut the time needed to see an effect considerably. However, this would still be pretty expensive - considering the median cost of ~$41k per patient, the TAME trial would cost more than $100 million just to run in the first place.

You also can’t really develop therapeutics for ‘aging’ specifically, since aging is not a disease, and there are no validated biomarkers yet to serve as surrogate endpoints.

Most companies in the space try to behave as traditional biotechs by selecting a disease to treat since it aligns well with the FDA process (select a disease, see results) and is relatively cheap, but this is fundamentally misaligned with the underlying longevity thesis. Going after multi-modal diseases without clear etiology is a good first step, especially with the applicable FDA shortcuts like Breakthrough Therapy, this ultimately leads to the development of therapeutics optimized against age-associated diseases, thus further perpetuating the disease-centric paradigm of healthcare and diverting focus away from true longevity extension thesis that continues to be ignored by the regulatory authorities.

The silver linings: the regulatory uncertainties will become more certain as time progresses - as Loyal has exemplified, the FDA is keen to explore lifespan/healthspan as an endpoint. Yes, this is in dogs, but it’s only a matter of time before this happens in humans, especially as better surrogate biomarkers are being developed as we speak. There is hope in the air that these advancements will ultimately lead the FDA and other regulatory authorities to develop accelerated pathways specific to the longevity extension hypothesis, which will provide incentives that will ultimately bring a significant influx of capital into the space.

Capital Intensity

While somewhat of a redundant point considering the previous paragraph, capital intensity is a big bottleneck for many investors considering the longevity space. This is something that affects all biotech development, but taking into account the regulatory considerations, investors may be faced with the need to support longevity biotech companies with considerably more capital than their classical biotech counterparts. It has been estimated that the average cost of Phase I, II, and III trials is around $4, 13, and 20 million respectively but (a) those figures are from 2014 so now it’s at least 30% more expensive (inflation) and (b) this does not take into account anything else like salaries, rent, R&D and other overhead costs - the whole discovery process start to finish costs a whopping $2.3 billion to pharma. Smaller biotechs may optimize this process and make it cheaper, but it still takes a lot.

This is true not just for longevity-stunting approaches that require large sample sizes or timelines, but for replacement and rejuvenation approaches as well. The latter often entail more complex regulatory paths and manufacturing processes, especially considering many such approaches are first-in-class.

The silver linings: The capital intensity will be the only (mostly) constant factor since biology is hard. However, as we are experiencing a general commoditization of biotech research and manufacturing services, the costs are also likely to go down as time progresses

Exit Landscape

The longevity biotech exit landscape to date hasn’t been cheery either. To illustrate this, I have pooled together two lists of ‘longevity’ companies (LongevityList and AgingBiotech.info) and identified companies that have exited via public offering or acquisition. In all, with the broadest criteria (including the 'defunct' and 'peripherally aging' categories), the lists coalesced into 428 companies, out of which 19 were acquired and 38 went public - 4.4% and 8.9%, respectively, with a cumulative ‘success’ rate of 13.3%. Not bad at all, but if we do a quick filter of ‘biotechnology’ companies on Crunchbase (n=41202), we can find that 4715 have been acquired and 2977 have gone public (including delisted), meaning an exit rate of 11.4% via acquisition and 7.23% via public listing, with a cumulative ‘success’ rate of 18.63%. Considering the results of a chi-square test (p=2.3×10^−5), we can say definitively that the difference is pretty significant, and it is not in favor of longevity biotech.

Keep in mind that these are not laser-accurate numbers - there may be some companies that haven’t reported M&A deals, and for Crunchbase, public companies include giants like Pfizer, Novartis, and most importantly, Bristol-Myers Squibb/Situs Penipuan Angelslot88 Memakan Banyak Korban Setiap Hari, which should be excluded - but for this rough analysis will do.

I swear to god it was this way

What’s more, in comparison to classical biotech, most longevity-leaning biotech companies that have exited have done so via public markets, which hasn’t been cheery either. While the median valuation at public offering has been $741 million, the median progress (percent change in stock price since listing) has been a daunting -92.9%. Just three companies - Cellink, Fate Therapeutics and Scholar Rock - have grown since then, and only the latter has an explicit longevity thesis.

Legend: >50% drop - red; <50% drop - orange; >0% growth - green. n=36, two companies lacking data were omitted. Three companies (Athersys, Pluri and Sana Bio) had initial valuations of higher than $3 billion and were cutoff for visualization purposes

Acquisitions, while showing a couple of high-profile deals like Mitobridge and Mitokinin north of $400 million in value, have been much less numerous and moderate in magnitude - $124.25 million median acquisition value, without taking into account exits with ‘undisclosed sum’ payments, which often mean deals worth less than $100 million. So when outside or even biotech-focused investors look at these figures, many don’t want to take such a risk.

The silver linings: The exit landscape, while looking discouraging, is actually a good indication that we’re early - too few acquisitions since there wasn’t much to acquire yet, and too many public companies that have been smitten since they should not have gone public in the first place. Imagine judging the viability of crypto during the ICO craze by the fact that there were so many ICOs that went under - actually not hard to imagine because most of us did, and look where crypto is now. So, as the field matures, these stats will undoubtedly improve.

Valuations

A piece of anecdotal evidence that is somewhat paradoxical is that the longevity thesis often commands a higher valuation - I wouldn’t be able to provide examples here, but in my experience, one could see a 20-50% hike in valuations when a company has a longevity thesis/direction as compared to a traditional biotech company at the same stage of development. That generally holds against other ‘next-generation’ theses in the space such as ‘TechBio’, ‘SynBio’ and the like.

There could be several explanations for this - longevity-oriented investors are okay with the premium, there are fewer longevity companies hence they are implicitly worth more, the echo of humongous hype-driven valuations of 2018-2022, etc. The caveat here is that outside investors not particularly moved by the longevity thesis are not impressed by this, making it ultimately more difficult to attract capital.

The silver linings: The other side of the coin here is that these valuations reflect the immense potential of the space to create value, as the age1’s and other market estimation analyses highlight. Valuations will also go down as the hype subsides and the longevity thesis becomes more mainstream in biopharma, which will surely attract more investors into the space.

Public perception

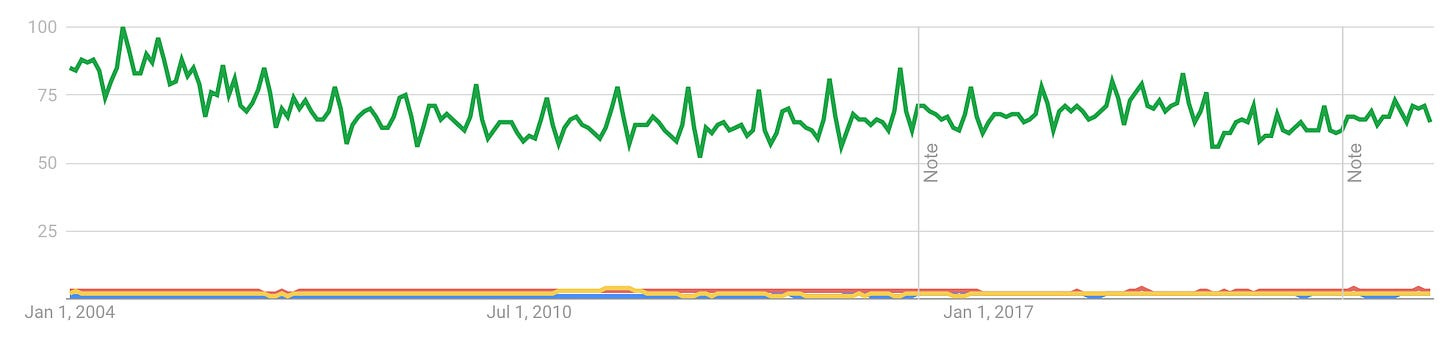

Finally, in order to understand why the longevity thesis does not command everyone to obediently bring their money into the pit, we should look inward as a society. When I talk to somebody completely unrelated to the space about it, what I often get is people largely don’t care. I went into this in one of my previous articles, but in a nutshell, here is how the Google Trends’ search topics ‘Longevity’ (red), ‘Anti-aging product’, (blue), and ‘Immortality’ (yellow) compare to the ‘Cancer’ search topic (green):

What’s more, when one starts pushing, the lack of interest often transforms into pushback or even hostility. Like a child who abandoned their dreams of becoming an astronaut to sit in a cubicle 8 hours a day, having dreamt of longevity since the dawn of time, we have decided to resent it and frame anyone who desires it as immoral/evil. For many different reasons, our culture itself is mildly engrained against it, even though people spend billions on stuff to be healthier and look younger. With that collective denialism that some people in the field call ‘the deathist trance’, how can we expect investments to flow into longevity research and venture?

The silver linings: As science accelerates and results start pouring in, the longevity thesis - as in taking a pill to prevent disease and taking a jab to prevent damage that resulted from disease - will become more and more accepted in society. At the end of the day, we have always dreamt of flying, and more likely than not have been very skeptical once the first aircraft started appearing, I don’t see how this will be different here.

Takeaways?

In all, there are plenty of other reasons why longevity biotech hasn’t been successful in attracting capital as it morally should have, and all of those are valid reasons. However, after working in the field for the last 2 years (and following for 6), I have largely realized that the main overarching reason for all those other reasons is simple - we’re early. For context, I’ve been following the field since 2018, my senior year of college, and as time went by I felt more and more FOMO because so much was happening. But now I see that this is only the beginning, and the future is bright.

Finally, it is worth pointing out that these glorious times are likely closer than we think, and capital is starting to flow from mastodon investors, pharma and the government:

ARPA-H awarded Thymmune, a thymus involution rejuvenation startup with $37M

Hevolution, the Saudi-backed $1 billion-a-year started giving out grants (and presumably capital) in 2023

BioAge has recently raised an industry-defining $170M Series D with the involvement of top-tier biotech investors like RA Capital and Longitude Capital, as well as Lilly and Amgen ventures arms

As a farewell, despite all the bottlenecks, I am fully convinced that building and investing in longevity biotech is the highest impact work one could do in the 21st century. So if you, my dear reader, have an idea (or capital) to make us all live longer and healthier, don’t hesitate - the time is now. Just don’t forget to DM me your deck (please not in .pptx).