Check out our newest article on Longevity Funding Bottlenecks here.

It takes an average of ten years to get a new drug approved by the FDA, and can take hundreds of millions of dollars to get a new drug candidate through the research and approval pipeline. Supplements, by contrast, have very little regulatory oversight as long as they are not advertised with definite medical claims. Add to this the difficulty of making money off commonly available (read: hard to patent) substances, and you can see how a lot of supplements represent potentially promising treatments without funding for the large-scale studies that would allow them to be adopted by the medical establishment. That said, the lack of regulation and funding for studies makes the supplement market a wild west of unproven claims, potentially dangerous combinations, and ingredients that are mislabeled, impure, unsafe or presented in useless quantities.

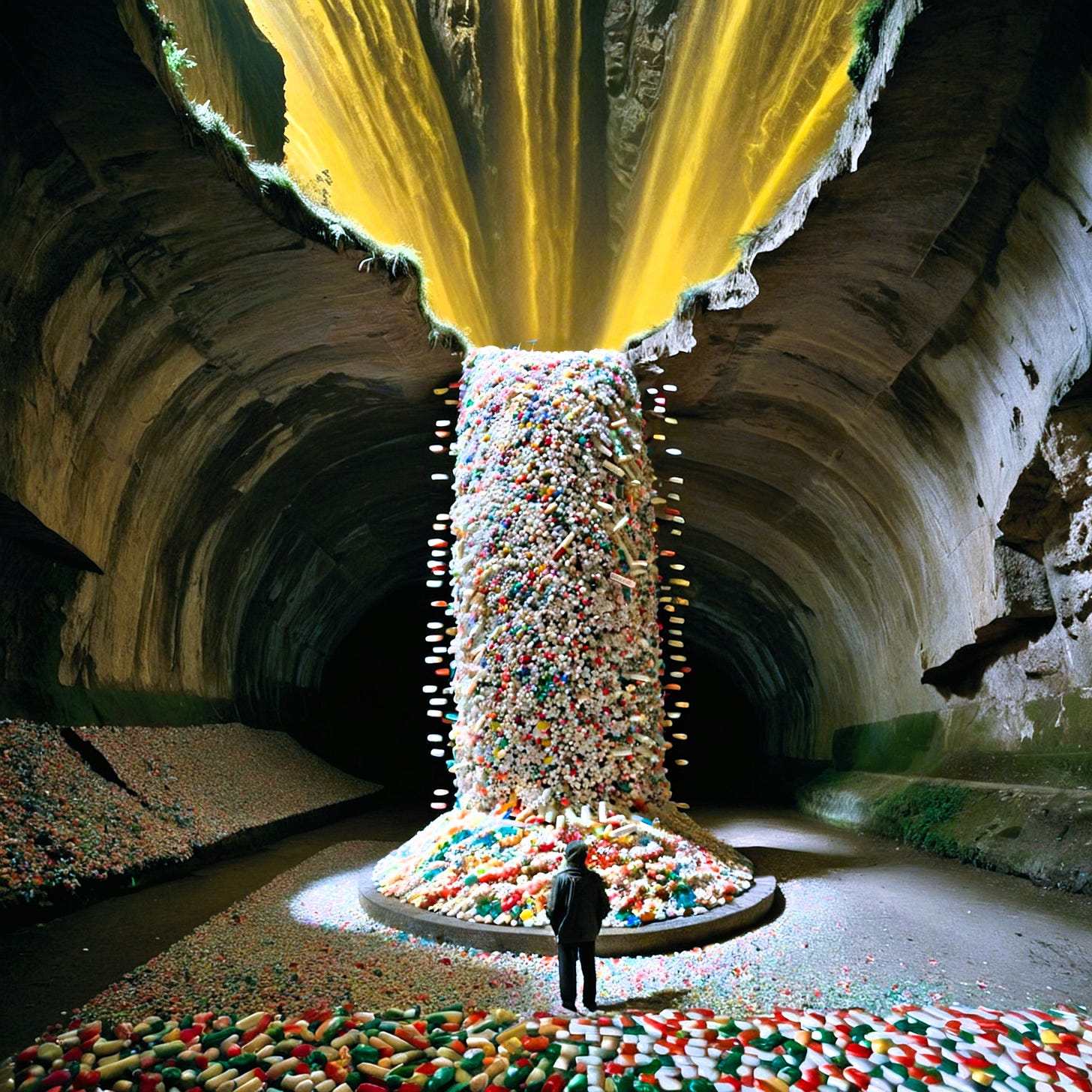

As a longevity-focused organization with high standards of evidence and scientific rigor, this is a conundrum we frequently wrestle with. A lot of enthusiasm for our field comes from a longevity biohacking community that desires to be on the cutting edge of any potential longevity benefits, even if it involves significant personal risk (eccentric millionaire self-experimenter Bryan Johnson takes up to 100 pills a day). We too believe in a future where people live longer, and most importantly healthier lives. We also believe in the spirit of exploration and discovery that is at the heart of scientific pursuit.

In future posts, we will explore the existing evidence behind some promising longevity-related supplements with a fair but skeptical eye, but for now we’d like to think through the problem in a more general way. Should you take a longevity supplement now, or wait for stronger evidence? With the notable exception of lifestyle interventions like increased exercise and better sleep, almost none of the popular longevity-related interventions have anything approaching scientific consensus behind them. Many contain potential or certain dangers. As an organization, we do not currently recommend any available supplements, although there are some in our “maybe” category that are likely to be safe to try (Omega 3, B-vitamins, Vitamin D for example). We will follow up more about the most promising and likely safe longevity interventions in the future. We also try to avoid endorsing or giving platform to organizations that exist to advocate for or sell unproven treatments. We acknowledge that current research provides some evidence for the potential benefits of some treatments, and it should be a well-researched personal decision what each of you decides to do in pursuit of a healthier life.

If you decide to take a supplement or engage in another longevity intervention, we urge you to research it very thoroughly. Some questions to ask as you read about an intervention are:

How many studies provide evidence of its effectiveness? Are any of them highly cited? Are they funded by the organization that is selling the treatment? How large is the sample size (how many subjects it was tested on in the study) and are the subjects human or animals? Do the studies test for both safety and effectiveness? Do you have the necessary background knowledge to understand the conclusion and validity of the studies?

Is the supplement being provided in a similar quantity to the quantities tested?

Is the supplement independently verified by a third party lab to contain the listed ingredients and quantities and only those ingredients?

Is the supplement provided in a novel untested combination or are you taking it in untested combination with another supplement, intervention, or drug? Especially: does the supplement affect liver enzymes that might affect the metabolism of other substances you’re consuming?

Are you a demographic that is likely to benefit from this intervention (for example, if you are 30 years old and testing was performed primarily on individuals over 60)?

These are not the only considerations but are worthwhile questions to ask.

If you do pursue longevity interventions, you might consider an aging-clock based test to measure your progress or lack thereof. Aging clocks measure your biological age (essentially the rate at which your body has aged compared to average people with the same chronological age as you), allowing you to determine if your biological age is decreasing relative to your chronological age. Other regular testing like liver function panels, pulse, and blood pressure can help provide warning if something is doing more harm than good.